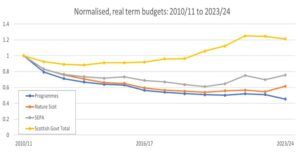

The publication of the draft Scottish Government Budget 2023/2024 prompts another look at what gets spent, in real terms, on core environmental protection and management in Scotland. The plot below (Fig.1) shows that from financial year 2010/11 through to the current proposal for 2023/24, there continues to be sustained underfunding.

This period is chosen as it marks the beginning of the public sector austerity measures, following the global financial crisis of 2008.

Both NatureScot (formerly SNH) and the Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA) receive core funding, each year, for their operational activities. Notwithstanding small increases this year, the funding for NatureScot has declined by 40% over the period. For SEPA the reduction is currently about 20% but has, just a few years ago, been as much as 40% as well.

The Scottish Government also contracts out policy-driven and policy-related environmental research to gather scientific evidence and find innovative solutions to our pressing problems. This is delivered through a rolling, tendered, and competitive, core programme which, in effect, underpins the research capability of major providers like the James Hutton Institute, Moredun and Scotland’s Rural College, as well as funding several multi-partner Centres of Expertise, such as CREW, for water management, and ClimateXChange, for climate policy. This research budget has declined by almost 60%, in real terms, over the past 13 years.

The graph below shows that spending in these areas has been disproportionately cut in comparison to the overall Scottish budget. While some increases to the overall budget reflect the devolution of additional powers, and subsequently pandemic-related spending, this does not explain why these environmental agencies have been deprioritised over this period.

It’s worth noting that trimming this environmental spend in Scotland has actually delivered less than 0.2% savings in the overall Government budget. As a proportion, the three environmental components shown here declined from 0.55% of total Scottish budget in 2010/11 to a minimum of 0.25% in 2022/23.

|

Fig.1 Normalised, to financial year 2010/11, real-term, budgets for the public environment research programme, for NatureScot, SEPA, and total Scottish Government. Source budget summary & updated from yearly budgets. |

The research providers, of course, have the opportunity to bid elsewhere for competitive research grants and, on the whole, are very successful in bringing inward investment and added value to the science base. The Scottish Government funds, however, are focused specifically on Scottish environmental issues that support Scottish policy and deliver public good. Other research funds are not locally focused and, for example, those from the European Commission are now seriously jeopardised by Brexit.

SEPA derives around half of its income from separate cost-recovery schemes, with charges imposed on businesses who hold licences to discharge to the environment. These charging schemes are approved by the Scottish Government and have not always kept pace with inflation. In 2010/11 this income was £34.1M and in 2020/21 was £42.0M, a real-term reduction of 14%.

These deep, and prolonged, cuts have an inevitable impact on staffing. For example, NatureScot had 728 staff in 2011/12 and only 594 staff in 2020/21. The search for a new NatureScot Chair began this week and one of the first issues she or he will have to deal with is how to address the lack of resources for the body charged with addressing the nature crisis. High quality environmental regulation and management cannot be delivered without professional staff, using sound science, informed by robust research and evidence. During periods of financial constraint, it is all too easy to delay building maintenance, to cut training and quality management systems, to delay replacement or upgrading of equipment, limit site visits, and reduce monitoring. In the short term this may be inevitable but, in the longer term, it undermines the capability to deliver operationally well-informed solutions. As cuts continue, then excessive management time is devoted to further cost reductions, restructuring and reorganisation, closure of premises, and ultimately delivering voluntary severance programmes. All this detracts from core duties and increases operational risks.

At the same time, Scotland’s environment is deteriorating. Almost 50% of ecosystem services are in decline; the percentage of nature protected sites in favourable condition has declined from 80% in 2017 to 78.3% in 2021; the index of terrestrial species abundance slumped from 98 in 2010 to 68.7 in 2016; Scotland is ranked 212 out of 240 countries for biodiversity intactness; the reported ecological status of Scotland’s rivers has dropped.

So, has wider environmental concern been refocused by Scottish Government away from the “nature crisis” towards the “climate emergency”? The Scottish Government puts the nature and climate crises side by side and requires climate mitigation and adaptation in every routine budget and work programme. Despite this, however, a recent report shows that total emissions associated with the Scottish Budget for 2023-24 will be 8.8Mt carbon dioxide equivalent, which is higher than in 2010-11. This is reflected in the recent progress report from the UK Climate Change Committee, which says “The Scottish Government lacks a clear delivery plan and has not offered a coherent explanation for how its policies will achieve Scotland’s bold emissions reduction targets”.

Scottish Government states that “Scotland’s natural environment is central to our identity as a nation” that “we will play our full part in responding to the global climate and nature crises” and “through our work, our country will be transformed for the better. Our natural environment will be restored.”

As LINK has stated, Scotland needs more robust environmental scrutiny, audit, challenge, targets, funding most certainly, and formalised accountability and delivery to do that.

Contributed by one of LINK’s Honorary Fellows, this blog provides analysis of budget allocation to the environment sector in 2023 – 2024.