The Big Tree (Scotland) Winner of Woodland Trust Tree of the Year Contest 2017 (Mark Ferguson)

Scotland faces both climate and nature emergencies. Woods and trees are a huge asset on each front so protecting them is key, especially our irreplaceable ancient woodlands. The planning system has an essential role to play in ensuring that protection, so we can be climate ready as a nation while protecting and enhancing biodiversity. Scotland’s new Draft National Planning Framework (Draft NPF4) presents landmark policy changes that could halt further loss of ancient woodland and trees. We must seize this moment and ensure these policy changes are retained in the final version to become planning reality.

What it means to be ancient

Very often when people think about what defines ancient woodland, they will be thinking about old trees and woodlands which have existed since the 1750s (as categorised by Scotland’s Ancient Woodland Inventory). But some of these patches could have been continually wooded for many hundreds or even thousands of years more. They are relics in the landscape quite often holding clues to our cultural past, remnants of woodland industries and historical management.

Ancient and veteran trees are no less impressive and awe-inspiring than our ancient woodlands. Scotland’s oldest specimen, the Fortingall yew, is believed to be roughly 3,000 years old. But to be ancient or veteran, trees needn’t reach such extremes, so long as they are old for their species. While size can be a sign of their age, if an individual has faced tough conditions, as they often do in Scotland, an ancient tree may not be that big at all. Instead, they can be recognised by their gnarly bark, hollowed-out trunks, cavities or reduced crowns and the organisms they are usually bursting full of.

Kinclaven, Autumn October 2018 (Niall Benvie / WTML)

Abriachan Woods Scotland, Summer, (Paul Glendell / WTML)

The state of ancient woods and veteran trees

The Woodland Trust recently published ‘The State of the UK’s Woods and Trees 2021’, presenting key facts and trends focusing mostly on natives, including those that are ancient. The report highlighted the importance of these habitats and organisms for a happy and healthy society and for nature and climate. It presented data showing average amount of carbon stored per hectare in Scotland’s ancient woodland are 31% higher than the average for all woodland types, and there is enormous potential for carbon stored in ancient woodland to double over the next 100 years.

Yet the report’s key findings note that despite woodland cover gradually increasing, existing native woodlands are isolated and in poor condition. The last remaining 30,000 ha of Scotland’s rainforest on the west coast is one such example that is threatened with further loss if action is not taken now. There is also a reported widespread loss of ‘trees outside of woods’ including individual ancient and veteran specimens, to make way for inappropriate developments. Scotland’s ancient woodland has been reduced to cover just 1-2% of the land. It continues to be eaten away by inappropriate development, poor management, Invasive Non-Native Species (INNS)and grazing animals, particularly deer.

Development, Planning and Trees

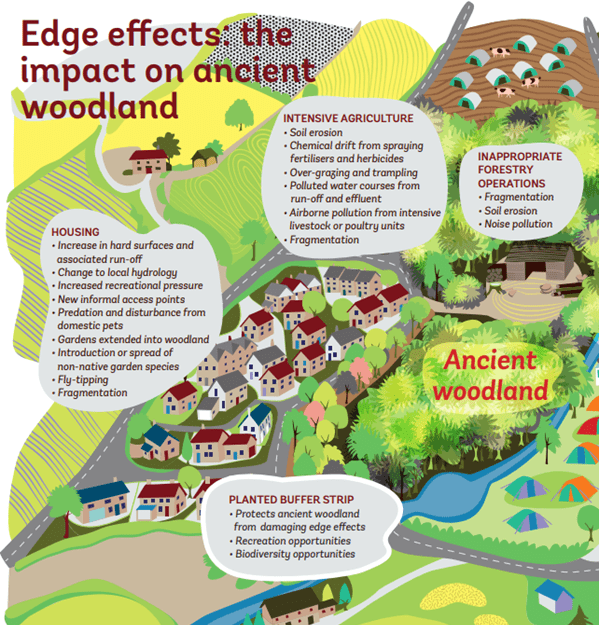

Development does not only lead to the loss of ancient woodland and veteran trees it directly displaces. In many cases it can also harm adjacent woods, which may be spared the bulldozer and the saw, but nonetheless suffer a slow decline in ecological condition over time. This effect of development is often overlooked. Declines in ecological condition happens over extended periods of time and this is perhaps why people find it hard to understand. It’s not an immediately quantifiable loss and due to the long-life cycles of trees it’s not at once visible. Our baselines shift, and we forget how these woodlands once looked and felt, but gradually they decline and slowly quieten, until finally they disappear.

Figure 1. Edge effects: the impacts on ancient woodlands (cropped), The Woodland Trust – Planners’ Manual for Ancient Woodland and Veteran Trees – Scotland.

But well-devised planning can protect trees from inappropriate development. Whether that’s high-level protections outlined by Scottish government or developers integrating buffer strips and root protection zones into their development designs.

However, protections outlined to date by the government have been insufficient to protect ancient woodland and ancient and veteran trees. Whilst planning policy highlights the irreplaceable nature of these habitats, as of July 2020 the Woodland Trust was aware of 274 ancient woodlands threatened by development. The real figure is likely higher.

Ancient Woods and Trees in Scotland’s Fourth National Planning Framework

The Fourth National Planning Framework presents an incredible opportunity to strengthen the protections outlined for ancient woodlands and ancient and veteran trees in planning policy.

When the Draft NPF4 was published in November 2021 it marked a leap forward in ancient woodland protection policies saying, “Development proposals should not be supported where they would result in: any loss of ancient woodlands, ancient and veteran trees, or adverse impact on their ecological condition.”

This is a huge step forward for several reasons.

Current planning policy is more ambiguous and does not set the foundations for halting any further loss of ancient woodland or ancient and veteran trees. Whilst we have not yet seen the draft NPF4 policy in action, it provides more clarity and should hopefully eliminate development as a threat.

The draft NPF4 text also appears to place the same protection on ancient and veteran trees as it does ancient woodland and takes account of impacts on their ecological condition. Considering ecological condition is the kind of forwarding thinking that will be necessary for tackling the nature crisis and opens opportunities to think about the indirect impacts of development that can lead to declines in ecological condition and their eventual loss when considering planning applications.

There are still areas that need addressing. For example, the continued allowance of habitat fragmentation and the need to properly resource local authorities required to implement these policies. But the Draft NPF4 has reignited my hope that what remains of our precious ancient woodlands and ancient and veteran trees can be preserved. It is just a draft though, so we will keep on working and pushing government and MSPs for robust ancient woodland protections until they have become a reality.

Conclusion

Development is not the biggest threat to ancient woodland in Scotland. Pressure from deer is a much deeper-rooted issue. Results from the Native Woodland Survey for Scotland (NWSS) reported ancient woodland cover had reduced by ~21,044ha between the recording of the Ancient Woodland Inventory (AWI) and the recording of the NWSS. Roughly 90% of that loss was most likely due to herbivore pressures in combination with the poor regeneration capacity of older trees.

However, threats don’t work alone, they are piling up to decimate our woodlands. Development can fragment habitats changing the climatic conditions inside them, so altering the species suited to live there. A new housing development may lead to garden waste thrown over the fence into ancient woodland. That waste may contain INNS, those may spread through the site damaging its ecological condition.

The multitude of threats present is leading to the decline of woodlands across the country. We are facing the very real fact that 97% of native woodlands are in poor ecological condition and less than 2% of Scotland is now covered by ancient woodland.

NPF4 provides us with the opportunity to eliminate one of those threats. We must seize it.

The Woodland Trust is running a campaign to ensure proposed ancient woodland and ancient and veteran tree policy changes are retained in the NPF4. Stand with us and support the campaign here.

Suzie Saunders is the Public Affairs Officer for the Woodland Trust Scotland and a member of LINK’s Planning Group.