Report concludes that we simply don’t know whether our current use of the seabed is sustainable or not

Calum Duncan reflects on the findings of a report commissioned by Scottish Environment LINK’s Marine Group to explore whether current conservation measures are sufficient to recover Scotland’s depleted seabed.

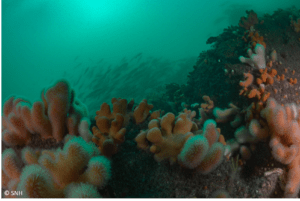

Photo: A rocky reef with dead man’s fingers and shoaling fish – Loch nam Madadh (image by SNH)

Regardless of Scotland’s future relationship with the EU, Environment Secretary Roseanna Cunningham last year committed to “carry through not just the letter of EU environmental law but also the underlying principles of precaution, prevention and rectifying pollution at source”[1]. Under the Marine Strategy Framework Directive, the Scottish Government, working with the other UK administrations, is committed to helping achieve Good Environmental Status (GES) for our seas by 2020. Scotland’s network of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) will make an important contribution, but not the only one necessarily needed, to ensuring the seafloor is healthy and can support sustainable use into the future.

During and following the first phase of fisheries management put in place for Scotland’s most vulnerable inshore MPAs there was much debate regarding those measures. At Scottish Environment LINK, we supported the measures put in place as proportionate to the ecological need of the sites and for them to achieve their conservation objectives and contribute to the wider recovery in the health of our seas. However, we also recognised that there was a wider picture in relation to how MPAs, and indeed any management measures to protect the seabed, should and could be contributing to attain GES under the Marine Strategy Framework Directive.

Among 11 ‘Descriptors’ or targets for what member states should be aiming to achieve, including closely related ones on Biodiversity (D1) and Commercial Fish and Shellfish (D3), is D6 ‘Seafloor integrity’ which requires that “Sea-floor integrity is at a level that ensures that the structure and functions of the ecosystems are safeguarded and benthic ecosystems, in particular, are not adversely affected”. There are a range of views on the extent of bottom-towed fishing and its ecological footprint, which came to the fore when putting in place fisheries management measures in the most vulnerable inshore MPAs, so we commissioned some work to help inform how far those fisheries measures put in place, and expected future management measures, would contribute to requirements to achieve seafloor integrity.

A healthy seabed that supports flourishing sealife, sustainable fishing, carbon storing, recreation (such as SCUBA diving and sea-angling), space for appropriately located offshore developments, nutrient cycling and other important services in perpetuity, and without declining, is after all what everyone wants. We understand that other activities will also impact on seafloor integrity, but recognise that Scotland’s Marine Atlas highlights fishing, along with climate change, as the most widespread pressures on our seas, and that there are some or many concerns regarding the status of most habitats around Scotland. We also acknowledge that DEFRA concluded “the spatial extent of damage from bottom fisheries is considered to far outweigh the contribution of other sources of this pressure”[1] and that the MPA measures primarily address the benthic footprint of fishing activity.

In a new report the team of Dr Charlotte Hopkins and Dr David Bailey at Glasgow University unpacked the complex topic of seafloor integrity and concluded that “it is impossible to say whether current levels of exploitation or extent of spatial management are consistent with GES”. The report acknowledges widespread consensus that mobile fishing gear “can destroy or seriously degrade some types of seabed such as maerl and cold water corals”, but the picture is less clear for other less vulnerable seabed types such as sedimentary continental shelf habitats. They then go on to state that “What is very likely is that much of Scotland’s seafloor is currently modified from a natural state, but what the relevant natural state for each area of seafloor would be is not known…” and that “…the critical test is whether there is evidence that the seafloor retains the ability to recover [rapidly] to a natural state and therefore retains its ability for other uses. This is the relevant definition of sustainable use when applied to the seafloor”. The authors provide suggestions for how sustainable use might be assessed for Scotland’s seafloor which “…includes the use of existing or cheap-to-collect measures of state, using [nature conservation] (NC) MPAs or new [Demonstration and Research] (D&R) MPAs as experiments to test whether the seabed can recover”. The thinking on “what is sustainable?” raised by this report was discussed by Dr David Bailey in his keynote address to this year’s MASTS Annual Science meeting in Glasgow.

At LINK, we will consider further the findings of this independent report but with 2020 less than two years away, it seems likely we will not know by then whether “Sea-floor integrity is at a level that ensures that the structure and functions of the ecosystems are safeguarded and benthic ecosystems, in particular, are not adversely affected”. We welcome the emerging MPA network being put in place, new work to improve protection of Priority Marine Features outside of MPAs, commitment to establishing a deep-water marine reserve and the fact that there is a MPA Monitoring Strategy. This historic opportunity to use the MPA network, including D&R MPAs, to assess the sustainability of activities that can impact seafloor integrity, particularly the use of mobile fishing gear, must therefore firmly be grasped. However, this means that application of the precautionary approach becomes even more crucial whilst more evidence is being gathered, to ensure habitats and species are not adversely affected in the meantime by the decisions that are made on how much activity can or can’t take place on the seabed. Scottish Environment LINK Marine Group members remain committed to support any work that answers these fundamental questions of sustainability, so that the wider debate and marine management in Scotland can move forward on a firmer evidence base.

Calum Duncan is Marine Conservation Society’s Head of Conservation in Scotland and the chair of Scottish Environment LINK’s Marine Group.

[1] http://www.scotlink.org/wp/files/documents/LINK-PRESS-RELEASE_EEB-Annual-conference-2017.pdf

[2]https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/69632/pb13860-marine-strategy-part1-20121220.pdf