The deep sea, technically defined as the areas below 200 m water depth, is the largest Ecosystem on Earth but the least explored. Guest blogger Dr Georgios Kazanidis, Post-Doctorate Research Associate in Deep-Sea Biodiversity at the University of Edinburgh and the H2020 ATLAS project, shares some of his insights about this incredible environment.

Fig. 1 The Remotely Operated Vehicle “Holland I” deployed at sea. Image credit: Marine Institute (Ireland).

Deep-sea researchers often mention that we know more about the surface of the moon than the deep sea. Technological development, however, over the last decades has provided researchers with new marine equipment like remotely operated vehicles (Fig. 1) and manned submersibles which enable the scientific exploration of this vast environment. Now we know that our deep seas host a huge variety of organisms including among others microbes, plankton (e.g. jellyfish), polychaete worms in muddy abyssal plains, cold-water corals and sponges in reefs and seamounts, bivalves, crabs and tubeworms in hydrothermal vents and of course fishes, sharks and mammals (e.g. sperm whales) diving down to thousand meters water depth.

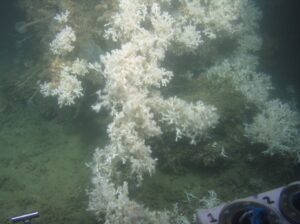

Several of these organisms and the settings that host them have been discovered and studied by scientists in Scottish deep-sea waters. For example, deep-sea sponges thrive in the Faroe-Shetland Channel and the Rosemary Bank Seamount, cold-water corals form reefs in the Mingulay Reef Complex (Fig. 2), which is one of the best studied cold-water coral reefs in the world, while coral gardens, burrowed muds and sea pens can be found in western Scotland. Deep-sea Scottish waters also host commercially important fishes like blue ling and orange roughy while sperm whales have been observed around the Anton Dohrn Seamount. Currently, a consultation is organized by the Scottish Government for the designation of a deep-sea Marine Protected Area in western Scotland (https://consult.gov.scot/marine-scotland/deep-sea-marine-reserve/).

Fig. 2 The reef-forming cold-water coral Lophelia pertusa at Mingulay Reef Complex, Outer Hebrides Sea. Image credit: J Murray Roberts (University of Edinburgh).

The mysteriously rich biodiversity of life found down there -deep waters are usually dark, cold and with little food- is often comparable to the stunning levels of biodiversity seen in tropical forests. Many of the deep-sea organisms grow extremely low and live for a long period of time, for example black corals in Hawaii live over 4000 years. These characteristics, however, make deep-sea organisms extremely vulnerable to physical damage from human activities e.g. bottom trawling, oil & gas activities and deep-sea mining. In addition, these species are threatened by ocean warming, acidification, deoxygenation and basin-scale changes in oceanic circulation all of which threaten the health status and ecosystem goods and services (e.g. climate regulation, food supply) provided by the deep sea.

Despite the substantial progress that has been made over the recent decades in our knowledge, there are still many knowledge gaps about the deep sea. For example, we have limited knowledge about the distribution of organisms and the habitats they form, their feeding habits and reproductive strategies and the dispersal of their larvae, to name a few. On top of that key questions about the resilience of organisms to climate change wait to be answered. Addressing these global challenges requires the establishment of international and intersectoral collaborations (e.g. among science, policy and industry) sharing knowledge and resources facilitating thus the conservation of deep-sea ecosystems. The H2020 ATLAS project (www.eu-atlas.org) is a transatlantic multi-partner collaboration among Europe, Canada and USA and is coordinated by the University of Edinburgh. ATLAS aims to advance our understanding about North Atlantic deep-sea ecosystems, improve our capacity to monitor and predict shifts in the deep sea, transform knowledge to effective ocean governance and stimulate Blue Growth. Scottish deep-sea ecosystems in Faroe-Shetland Channel and Mingulay Reef Complex are part of the ATLAS strategically-selected case studies serving the achievement of healthy, clean and productive deep-sea waters in Scotland and North Atlantic in overall.

For more information:

- About cold-water corals and deep-sea information, please visit http://www.lophelia.org/;

- About the ATLAS project, you are more than welcome to visit its website (www.eu-atlas.org) or get in contact with ATLAS coordinator Professor J Murray Roberts (University of Edinburgh; murray.roberts@ed.ac.uk).

Save Scottish Seas is extremely grateful to Dr Kazanidis for contributing this blog.