April 11th, 2025 by morag

This first appeared in The National, on Saturday 5th April 2025.

When Scotland votes in the Holyrood election next year there will be voters casting their ballot who were born in 2010, when Scotland had its fourth First Minister and was preparing for the fourth election of the devolution era.

Devolution is not new – and the fact that decisions on key areas like health, education and the environment are taken in Edinburgh, Cardiff and Belfast is now taken for granted.

But devolution has not been unchanging. While Holyrood has gained additional powers over its lifetime it has also, in the aftermath of the Brexit referendum, had its hands tied across a range of areas that were previously within the Scottish Government’s power.

The UK Internal Market Act was introduced to replace the European single market we were leaving, and sought to ensure that businesses could continue to trade across the UK. So far, so uncontroversial.

But in practice the UK internal market has had major implications – most notably in the case of Scotland’s planned Deposit Return Scheme, which faced an eleventh-hour intervention from UK Ministers and was subsequently paused and kicked into the long grass.

Deposit return is a well understood concept which exists elsewhere. Ireland introduced its scheme just last year. If Scotland had introduced its own scheme before Brexit we would all now be used to returning our bottles to the supermarket – but what is possible within the European single market was blocked within the UK internal market.

The UK Government is currently reviewing the Internal Market Act and has made positive noises about the need to improve its operation. This is a welcome opportunity to revisit legislation which has – intentionally or unintentionally – undermined the devolution settlement.

There is of course a need to harmonise trade across the UK. But there is also a wider point of principle at stake. The Scottish Government, with vast responsibility for the environment and able to set climate targets and to regulate a wide range of activities, should be able to introduce a recycling scheme.

The issues with the Act go beyond deposit return. Other policy areas have faced complications because of Internal Market rules, and straightforward steps like ending the environmentally destructive use of peat in garden compost, or banning rodent glue traps, have been dragged into a constitutional tug-of-war.

This is a result of the unnecessarily strict approach to managing the internal market. As the Act focuses on the trade of goods, it limits the ability of devolved governments to intervene at the point a product is sold. Even minor and proportionate measures, relating to areas of devolved responsibility, are blocked – and this can only be overturned by the administration in question seeking an exemption from the UK government.

One of the strengths of devolution has always been the ability of each nation to pursue its own priorities, to innovate, and to learn from each other. This was possible under the European single market without damaging trade across the UK. Now, the internal market is having a chilling effect across policymaking, with necessary measures not pursued or dragged into the bureaucratic and politically contentious territory of exemptions.

The environmental sector across the UK is united in seeing the Internal Market Act as an unnecessary blocker to action – a viewpoint shared by the constitutional experts who have given evidence on the review to Holyrood. A system which allows the devolved governments to take proportionate steps without first receiving permission from the UK government is possible. The UK Government has the chance to listen to these pleas and to redesign the internal market to respect devolution.

Dan Paris, Director of Policy and Engagement at Scottish Environment LINK

April 2nd, 2025 by morag

By Leigh Abbott, Nature for All Officer at Scottish Environment LINK

The final EDI Fortnight as part of the Nature for All project begins in less than a week’s time, and we are very excited to learn, share, and change our practices to put diversity and inclusion at the forefront of our work in the environment sector.

It will be held on the 7th, 8th and 9th, and the 14th and 15th of April, with extra special talks on the 23rd of April. We have a busy schedule with lots of requested online talks and workshops from our member organisations provided to you, for free! This includes:

- Six LINK member organisation talks on EDI to share, learn, and support each other.

- A session on neuro-inclusive leaders from Differing Minds, including a toolkit to take away with you.

- A workshop on supporting young carers and young people from low socioeconomic class, led by Caitlin Turner.

- A session on employing people on work visas, from an immigration consultant and Nourish Scotland.

- A webinar on supporting others with their mental health from Scottish Action for Mental Health (capped at 50 participants).

- A workshop progressing from last year’s Jo Yuen session, ‘From Awareness to Action’ (capped at 25 participants)

- A workshop on handling difficult conversations from the National Trust for Scotland (capped at 30 participants)

If you work for a LINK member organisation, you can register your place for the online talks and workshops via Eventbrite.

Why register?

Nature is for all, and nature needs all of us. The more voices we have to tackle environmental issues; the better the Scottish environment will be for it.

The scale of the climate and nature crises demands that it’s not enough to know about these issues – we need action to make the change we want to see, and for people to feel that they belong in the environment sector. Progress requires change and you will learn these skills via the talks, training, and workshops provided by the EDI Fortnight.

But don’t just take my word for it, here’s some quotes from our previous EDI Fortnight attendees:

“These events have been invaluable”

“The fortnight has been of great value to our organisation and we have saved all the slides and resources in our internal EDI folder to share the learning even wider. Thanks so much!”

“A more diverse insight into the world around me”

“Listening to the discussions gave me an opportunity to hear others worries and experiences which will help put anti-racism into practice by appreciating and understanding this better”

“I felt really comfortable to participate. It was also super informative and functional – I think everyone was able to take away some positive actions”

Remember: Every. Action. Counts. No matter the size.

So why not come along, share and learn alongside our members and try and make the environment sector the best place to work and volunteer, for everyone.

Register your place for the online talks and workshops via Eventbrite.

Top image: Ross MacDonald / SNS Group

March 19th, 2025 by morag

By Duncan Orr-Ewing, Convener of LINK’s Deer Group

Over the past eighty years there have been no less than seven separate Government-appointed inquiries into the “red deer problem”. By 2010, red deer numbers had reached an all-time high of 400,000 animals and the Red Deer Commission was merged with Scottish Natural Heritage (now NatureScot). The outgoing Chair of the Deer Commission said at that time “the current voluntary system has not evolved much in the past twenty years…if opportunities for reform are not taken then other approaches need to be considered”. In 2016 an SNH Report to the Scottish Government – Deer Management in Scotland – highlighted “we are not confident that present approaches to deer management will be effective in sustaining and improving the natural heritage in a reasonable timescale”.

In 2017 the then Cabinet Secretary for the Environment, Roseanna Cunningham MSP, announced that she was setting up an independent review on deer management in Scotland and stated “by setting up an independent group on deer management, encouraging SNH to use their full range of powers and improving deer management plans, we hope to address the main challenges and ensure we protect our environment and the interests of the public, as well as support the rural economy.”

In 2020 the independent Deer Working Group (DWG) published its report and made nearly 100 sensible recommendations for reform and modernisation of deer management systems and process in Scotland. In 2021 the Scottish Government responded to the DWG Report and accepted most of the recommendations, whilst also indicating that these would be implemented “as soon as practicable”.

In 2025, we finally have the promise of new deer legislation in Scotland as part of the Natural Environment Bill. This process started in late January with a Deer Management Round Table convened by the Rural Affairs and Islands Committee of the Scottish Parliament. The draft Natural Environment Bill including deer management reforms was finally published in February and we are pleased to be able to warmly welcome this progress.

The LINK Deer Group welcomed the chance to participate and has expressed its public support for the full implementation of the Deer Working Group’s recommendations.

Meanwhile, deer numbers of all four species of deer present in Scotland (red and roe deer are native species and sika and fallow deer are non-native) are now at record levels, estimated at one million animals. This population figure is based on official Scottish Government statistics compiled by NatureScot and the Strategic Deer Board. The Deer Working Group Report (December 2019) stated on page 38, under National Population Estimates that “there could be approaching a million wild deer in Scotland”. In The Herald newspaper on 22nd July 2022, Lorna Slater MSP stated “the population of deer in Scotland is now estimated to be in excess of one million….” and in an article in The Herald on 26th August 2022 Donald Fraser, Head of Wildlife Management at NatureScot was quoted as saying “there are around one million deer in Scotland”. Since NatureScot took on responsibility for deer management in Scotland the deer population has therefore effectively doubled.

So why does this all matter? Most people accept that deer are an important and iconic part of our natural heritage, and certainly everybody wishes to see their populations at healthy and sustainable levels. In most other similar countries to Scotland deer populations are managed to sustainable levels – usually involving statutory systems informed by good population data – as a natural and healthy food resource; to prevent damage to a variety of public interests; and to promote deer welfare.

Here in Scotland the situation is more acute as deer lack any natural predators; in our view we have over-relied on voluntary approaches led by private landowners; we have lacked public incentives for deer management; our venison market does not work well; and NatureScot has been reluctant despite Ministerial instruction (as above) to use the full range of its statutory powers for fear of legal challenge.

Voluntary systems of deer management have simply not delivered over a long period of time what is now urgently required. To give an example on the last point; Caenlochan in the Cairngorms National Park has had voluntary control orders under section 7 of the Deer (Scotland) Act 1996 with the relevant Deer Management Groups for over 25 years, and still deer numbers are well above sustainable levels, causing damage to the fragile montane habitats. According to the Deer Working Group Report, between 2006-18 over £3m was spent by NatureScot on section 7 agreements and of eleven section7s only one has concluded successfully.

Better models for reducing deer numbers at a landscape scale have been shown by the likes of the Cairngorms Connect project and the Great Trossachs Forest project in the Cairngorms and Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Parks respectively. The initiatives are partnerships between eNGO landowners, one private landowner in the form of Wildland Ltd, Forestry and Land Scotland and NatureScot.

The Scottish Government has recognised the interlinked climate and nature emergencies, as well as a producing a new Scottish Biodiversity Strategy. Sustainable deer management is a cross-cutting theme which delivers a wide range of public benefits including native woodland restoration; protection of public investment in peatland restoration; as well improving other habitats for wildlife. It also delivers human benefits such as prevention of road traffic accidents and a reduction in Lyme disease.

The LINK Deer Group supports full implementation of the Deer Working Group Report recommendations now set on in the draft Natural Environment Bill and we look forward to contributing to the further debate in the Scottish Parliament. For us, it is particularly important that NatureScot powers to intervene to reduce deer numbers are made more effective. We therefore support the proposals set out in the Bill to implement new, workable and more flexible powers to NatureScot to restore nature rather than to just prevent damage as previously. The approach of enhancement of habitats fits with the current needs of the Climate and Nature Emergency. We also think the time has now come for NatureScot to formally sign off and then monitor effective delivery of cull levels via Cull Approval Orders (recommendation 97 of the Deer Working Group Report) in important landscapes for conservation such as Scotland’s National Parks, Scotland’s Rainforest, Caledonian Pinewoods and other protected areas.

February 26th, 2025 by morag

The introduction of statutory targets to protect nature is a long-standing campaign demand of Scottish Environment LINK. We therefore welcome the publication of the Natural Environment Bill, introduced to the Scottish Parliament last week, which represents a vital opportunity to halt biodiversity decline and drive forward nature’s recovery.

Scotland’s Biodiversity Framework

The Scottish Government’s commitment to halting biodiversity loss by 2030 and achieving significant restoration by 2045 is encapsulated in the Scottish Biodiversity Strategy and accompanying delivery plan which was published at the end of 2024. The actions set out in this plan could, if appropriately funded and delivered effectively, make a significant difference. The Natural Environment Bill acts as a key piece of legislation to achieve these goals, establishing legally binding targets to restore our ecosystems, which should help to drive the action needed.

Creating a strong legal framework for nature recovery

Beyond the introduction of targets, the Bill covers other policy areas intended to support nature recovery. The Bill includes a range of measures to improve deer management, which is vital to allowing the natural regeneration of our native woodlands and strengthening National Parks. The Bill also includes changes to environmental protections such as Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA) and Habitat Regulations.

The Scottish Biodiversity Strategy and Natural Environment Bill sets the stage for urgent action to address Scotland’s biodiversity crisis. However, reaching these ambitions will require strong leadership, effective collaboration, clear targets and dedicated funding. We have outlined a summary and LINK’s initial response to key aspects of the Bill.

Statutory nature recovery targets

The introduction of statutory nature targets was a key ask of LINK’s post-Brexit campaign, Fight for Scotland’s Nature. The Scotland Loves Nature campaign has continued to push the Scottish Government to deliver the Natural Environment Bill and to build cross-party support for an ambitious approach to nature recovery.

The Bill itself is framework legislation – meaning that the key details and metrics of the targets will be set by Ministers afterwards. Biodiversity targets are necessarily complicated, and setting the specific targets in primary legislation would be difficult and potentially counter-productive. A framework approach was recommended in LINK’s 2023 report on nature recovery targets and, while there points of difference, the draft Bill broadly follows these recommendations.

As the Bill is drafted, the Scottish Government will be required to set at least one target covering the condition and extent of habitats, the status of threatened species, and the environmental conditions for nature regeneration. There is also a broader power to set targets on any matter relating restoration or regeneration of biodiversity.

Strengthening deer management

The Scottish Government estimate that there are as many as one million deer in Scotland, representing a potential doubling of the population in the past 20 years. This unnaturally high number of deer is damaging our environment by degrading peatland and suppressing natural tree regeneration.

We welcome Scottish Government’s proposals for modernising deer management as part of the Natural Environment Bill. These proposals, which build on the recommendations of the independent Deer Working Group (DWG) 2019 Report, aim to address the urgent need to manage deer populations in a way that helps tackle Scotland’s climate and nature emergency.

The government had initially consulted on a proposal to create Deer Management Nature Restoration Orders (DMNROs), aimed at addressing the ecological impact of Scotland’s large and increasing deer population. The draft Bill instead proposes to meet these objectives by making changes to existing powers under the 1996 Act, rather than the creation of a new power. LINK members will consider the draft Bill closely and work constructively to ensure the measures are strong and effective. LINK views the Bill as a critical opportunity to finally make considerable progress in managing deer populations sustainably and supporting biodiversity.

Enhancing the role of National Parks

The Bill makes changes to the aims and powers of National Parks, as well as setting up a fixed penalty notice regime for breach of park byelaws.

Existing legislation sets out 4 aims which National Parks are required to pursue (conserving natural and cultural heritage, promoting sustainable use of natural resources, promoting enjoyment and recreation, and promoting sustainable economic and social development). The Scottish Government had previously consulted on introducing an overarching purpose for the Parks, requiring them to deliver leadership on nature recovery and a just transition to Net Zero. LINK members had supported this proposal. Instead, the draft Bill modernises the language of the aims and proposes a new subsection with a non-exclusive list of activities to deliver on these, including restoring biodiversity and tackling climate change.

One notable change proposed is requiring other public bodies operating in a National Park to have regard to the aims and Park Plans.

Safeguarding Scotland’s environmental protections

The Bill proposes changes to EIA and Habitats Regulations, which are critical for protecting Scotland’s habitats and species. LINK members have some concerns about the lack of clarity regarding these proposed enabling powers.

LINK recommends that any changes be subject to full parliamentary scrutiny, with clear, narrowly defined purposes. The principle of non-regression should ensure that protections are not weakened. We will continue to engage with the Scottish Government and MSPs to ensure that the final Act is effective and fit for purpose.

Stay informed and take action

Public support is crucial to ensuring that the Natural Environment Bill delivers for Scotland’s wildlife. Sign up to the Scotland Loves Nature campaign for updates and ways to take action.

This Bill has the potential to be a game-changer for Scotland’s nature. By strengthening its provisions and ensuring accountability, we can take bold steps towards a future where biodiversity thrives. Together, we can make sure that this legislation delivers the nature recovery Scotland urgently needs.

Image: Sandra Graham

February 24th, 2025 by morag

By Vicki James, Protected Areas Coordinator at Whale and Dolphin Conservation

Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) are a critical tool for protecting important areas for cetaceans (whales, dolphins and porpoises) in Scottish waters. Around the UK, 11 MPAs have been designated specifically for cetaceans. However, research into the management effectiveness of these MPAs by Whale and Dolphin Conservation (WDC) reveals significant gaps in their management effectiveness, jeopardising their ability to deliver protection for the habitats and species they are intended to conserve.

The UK has committed to protecting 30% of land and sea for nature by 2030, with a goal to have 70% of MPAs in favourable condition by 2042. Yet, according to the JNCC, only a small proportion (83 of 374 UK MPAs) are moving towards their conservation objectives. These findings raise questions about whether these ambitions can be met without urgent changes.

Scotland’s MPAs have been designated to protect and support population recovery of harbour porpoise, Risso’s dolphin, bottlenose dolphins, minke whales and other marine life. MPAs include habitats important for survival of the species they’re designated for, providing essential breeding and feeding areas. These species are listed as Priority Marine Features (PMFs), which identifies them as a conservation priority for MPA designation. As the Scottish Government develops its National Marine Plan, fisheries measures and management of other activities, it has a key opportunity to lead in improving the management and effectiveness of MPAs.

Why evaluate the management effectiveness of cetacean MPAs?

MPAs are an essential tool for protecting cetaceans, but only if they are effectively managed. They can help safeguard crucial habitats, restrict and regulate harmful activities, and support nature recovery. However, threats from a range of anthropogenic activities including bycatch (accidental capture in fishing nets) and noise pollution (e.g. from offshore developments) will likely continue to cause harm if they are not adequately addressed.

Based on data available online, WDC assessed the UK’s 11 cetacean MPAs using the Marine Mammals Management Toolkit to evaluate the effectiveness of management measures, including stakeholder engagement and monitoring. The findings highlight significant concerns and underscore the need for immediate action.

Key findings:

1. Most cetacean MPAs lack a management plan: These are written specifically for each MPA to provide guidance on activities and ensure the conservation of the site’s protected features. In the UK, 90% of assessed MPAs are either lacking a management plan or the plan is an outdated one. In Scotland, only the Moray Firth SAC for bottlenose dolphins has an in-date management plan.

Management plans can inform decision-making by regulators and local authorities, helping to balance low impact use with conservation goals. Management plans for cetacean MPAs should outline strategies to manage activities such as noise pollution, bycatch and shipping, to prevent adverse effects on cetacean populations. They should also include an action plan detailing specific measures, responsibilities of organisations, and timelines to ensure conservation objectives are met, alongside a robust monitoring framework to regularly assess the condition of the site and the effectiveness of management measures.

MPA management plans are more detailed across a variety of activities compared to the Scottish Government’s consultation on fisheries measures. Fisheries measures across the MPA network can benefit cetaceans by reducing pressures such as bycatch, even if the focus of these measures may be other habitats or species. Therefore, MPA management plans provide wider benefits by addressing site-specific threats and prioritising conservation efforts for cetacean populations directly.

2. Noise pollution is not adequately addressed: Underwater noise from shipping, seismic surveys (use of airguns to survey the seabed), and offshore windfarm construction is the most poorly managed threat across all sites, based on available data, with minimal legally binding regulations or mitigation in place.

3. Harmful fishing practices are widespread: Bottom trawling, gillnets, and other damaging practices are still permitted within MPAs for cetaceans, resulting in risk of bycatch, habitat destruction, and prey depletion.

4. Insufficient monitoring is taking place: There are gaps in fine-scale and site-wide regular baseline monitoring of cetacean MPAs, which can be used to inform whether conservation objectives are being met as well as assessing the impacts of anthropogenic activity. The lack of regular, consistent baseline monitoring limits effective management and adaptive responses. Citizen science monitoring programmes, such as Shorewatch and Whale Track exist, which are partially addressing these significant data gaps. However, they should not be relied upon to fulfil statutory requirements for monitoring and impact assessments.

Recommendations for improvement

To ensure that harmful activities in cetacean MPAs are effectively managed to avoid or minimise impacts on cetaceans and other protected features, the following actions are crucial:

- Develop and implement management plans: Every MPA requires an up-to-date management plan to regulate activities, reduce harm, and monitor progress.

- Address noise pollution: Legally binding noise limits and use of proven mitigation measures, including for offshore windfarm development, are essential.

- Reform fishing practices: Introduce a management plan approach to restrict the most destructive fishing methods, including bottom trawling and gill nets, and minimise risks from lower impact gears e.g. through seasonal closures and gear modifications. In Scotland, there is the opportunity to do this through the much-delayed fisheries management measures (under the Marine Acts and Fisheries Act) in Scottish MPAs. In addition, the National Marine Plan 2 should incorporate fisheries management policies and give priority to restoration and protection of nature and biodiversity.

- Invest in monitoring programmes within MPAs to assess progress towards site conservation objectives and reduction of anthropogenic harms: There is a need to address the lack of baseline assessment of conservation status of priority species in sites, as well as monitoring of anthropogenic impacts. A robust monitoring programme needs to be implemented where the data is accessible in a standardised and timely manner to enable adaptive management.

The full report can be downloaded from WDC’s website

Image: Cath Bain

February 4th, 2025 by morag

Guest blog by James Curran (LINK Honorary Fellow) and Sam Curran

When I retired from paid work, I was eager to dive back into science. For years, I had an idea brewing that – if my hypothesis was right – would have important consequences for the planet, but I never had the time to explore it. Teaming up with my son Sam, we embarked on this journey, convinced that our simple idea must have already been investigated. Surprisingly, it hadn’t.

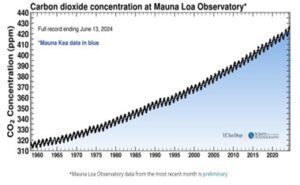

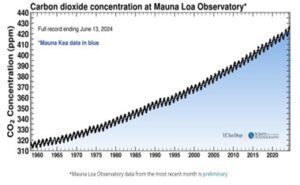

As independent scientists, we relied on publicly available data for our investigation. Fortunately, when it comes to carbon dioxide (CO2) levels in the atmosphere, there’s a wealth of open-access data. The longest record comes from the Mauna Loa Observatory, perched on top of a volcano in Hawaii, in the middle of the Pacific Ocean and fairly close to the Equator. This high-quality data record started in 1957 and continues to this day.

When plotted over time, these data form the well-known Keeling Curve. The saw-tooth pattern of the curve (Figure 1) is particularly intriguing. It occurs because most of the Earth’s land mass is in the Northern Hemisphere and, during the northern summer, the abundant vegetation of the North absorbs a huge amount of CO2 from the atmosphere.

When plotted over time, these data form the well-known Keeling Curve. The saw-tooth pattern of the curve (Figure 1) is particularly intriguing. It occurs because most of the Earth’s land mass is in the Northern Hemisphere and, during the northern summer, the abundant vegetation of the North absorbs a huge amount of CO2 from the atmosphere.

In the northern winter, some of this CO2 is released back into the atmosphere through natural biodegradation of dead vegetation, but a portion remains locked in roots, soil, and dormant woody matter. The portion of CO2 drawn out by vegetation and locked away is known as natural sequestration. The overall curve of CO2 concentrations rises year-on-year, of course, due to the additional anthropogenic CO2 emissions that we pump out continuously.

For our research, we focused on the curve’s saw-tooth pattern because it is a direct reflection of the overall health of the Earth’s biosphere and, particularly, its ability to provide some balance against CO2 emissions.

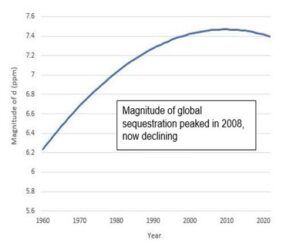

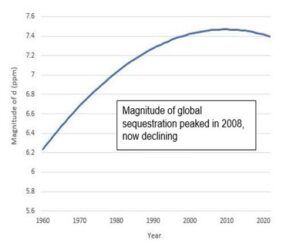

It is worth noting here a widely held belief that sequestration is increasing globally due to a) warming temperatures that encourage vegetation growth, especially in sub-Arctic regions, and b) higher atmospheric CO2 acting as a fertiliser of plant growth. However, it’s also acknowledged that sequestration will likely decline at some point in the future due to heat stress, wildfires, drought, storms, floods, and the spread of new pests and diseases. Enhanced seasonal permafrost melt may also release additional CO2 into the atmosphere.

In 2016, we published a couple of short peer-reviewed articles relating to this topic. Now, almost ten years later, it seemed like a good time to validate our earlier, tentative findings. Our third paper, recently published, reinforces the earlier and alarming finding that natural sequestration peaked in 2008 (the earlier work suggested 2006) and is now declining. It had been increasing at 0.8% per year in the 1960s but is now declining at 0.25% per year. To put this in perspective, sequestration would have increased by half in 50 years, whereas it would now decline by half in about 250 years. Does this matter? Absolutely.

Currently, atmospheric CO2 increases by about 2.5 parts per million (ppm) each year. If the biosphere’s sequestration ability had continued growing as it did in the 1960s, the annual increase would now be smaller at +1.9 ppm per year. That’s a big difference.

Currently, atmospheric CO2 increases by about 2.5 parts per million (ppm) each year. If the biosphere’s sequestration ability had continued growing as it did in the 1960s, the annual increase would now be smaller at +1.9 ppm per year. That’s a big difference.

Right now, just to make up for declining sequestration, anthropogenic emissions would need to fall by 0.3% per year. This is substantial, considering emissions have been increasing at roughly +1.2% per year.

These damaging effects will only get worse as the decline of sequestration is accelerating.

Everyone reading this blog will well understand the implications. The climate and nature emergencies are locked together.

It’s urgent that every effort is made to rebuild biodiversity and associated ecosystem services, including sequestration. Deforestation must stop. Nature restoration must be encouraged. Forest fires must be prevented. For large-scale habitats, which are more resilient and offer enhanced ecosystem services, defragmentation must be prioritized. Soil must be nurtured. Timber and fibre products must be reused for as long as possible, as part of a wider circular economy.

All this in addition to an end to burning of fossil fuels – of course.

The hypothesis we held for many years, as feared, has proven correct. Retirement may be upon me, but for my son, my granddaughter – for all our loved ones and for future generations, the need for action grows ever greater, ever more radical, and ever more urgent.

For further reading, see the short research article.

Photo by Roxanne Desgagnés on Unsplash

January 27th, 2025 by morag

The way that we use the land underpins much of our lives and the ways that we experience the places around us. How Scotland’s land is owned, used and managed is not only central to the economy and the natural environment, but it is key to the wellbeing of individuals and communities.

Land use planning is especially important when it comes to tackling the twin crises of climate change and biodiversity loss. The ways that we farm, where we build our towns, and how we manage our natural resources all have profound impacts for wildlife and for greenhouse gas emissions. In order to make the progress necessary to achieve net zero by 2045 and meet our nature restoration targets, we need to change the way we use land in Scotland.

With so many interests to balance, the Scottish Government produces a Land Use Strategy (now in its third edition) to outline high-level principles and a long-term vision for sustainable land use. Transferring this ambition to action on the ground isn’t easy, and this is where Regional Land Use Partnerships, or ‘RLUPs’, come in.

RLUPs were intended to bring together the relevant stakeholders within a region to work in partnership to optimise land use in a fair and inclusive way. These partnerships included representatives from local and national government, communities, landowners, land managers and other stakeholders who would help shape land use decisions in light of the principles and objectives of the Land Use Strategy. Through collaboration, it was hoped that these partnerships would develop a framework for land use that would meet both local and national objectives and support Scotland’s transition to net zero by 2045.

To ensure their effectiveness, the Scottish Government launched a series of pilot projects before committing to coverage across Scotland by the end of the next Parliament. Two pilots (initially called ‘land use strategy pilots’) ran between 2013-15, followed by a further five pilots with expanded remits between 2021-23.

With the pilots now complete, the question is: where do we go from here?

To help review the success of RLUPs and consider the future of strategic land use planning in Scotland, Scottish Environment LINK’s Land Use & Reform Group commissioned a report by Brady Stevens of SAC Consulting.

This new report emphasises the potential for Regional Land Use Partnerships (RLUPs), which, if given the necessary support, it sees as a fit-for-purpose model for future land use planning. The report also highlights a series of recommendations for the Scottish Government that could enable Regional Land Use Partnerships to achieve significantly greater impacts. These include, among others, a recommitment from the Scottish Government to the model, the rollout of RLUPs across Scotland, and the provision of appropriate resources to these partnerships.

Importantly, the report argues that Scotland already has the basis of the infrastructure needed to deliver its environmental objectives as part of a strategic approach to land use, and there would be considerable benefits in strengthening the ability of RLUPs to influence decision-making around land use, particularly in relation to public and private investment in nature.

As the report notes, “the most expedient route to impact does not involve reinventing the wheel. The key need is for people who are enabled to act as connectors, joining national targets and existing resources with local groups who have the skills and connections to get the work done.”

You can see the full list of recommendations and read the report in full here.

Top image credit: Sandra Graham

January 21st, 2025 by Miriam Ross

We urgently need to help Scotland’s seas recover. On paper, Scotland has a network of marine protected areas, intended to help conserve our fantastic ocean wildlife. The Scottish government is required to design and implement fishing restrictions for each marine protected area. But these crucial protections are more than ten years overdue.

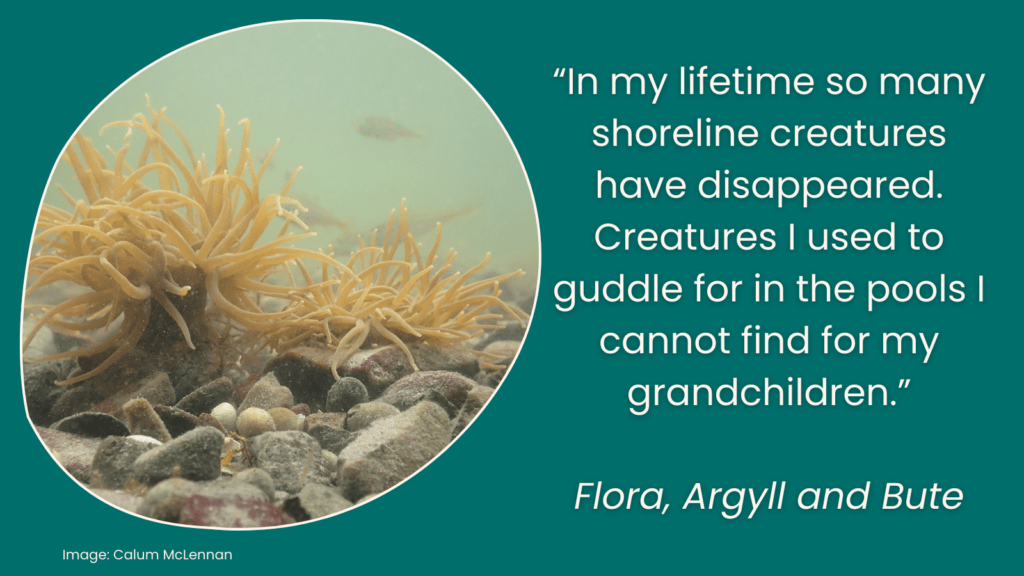

Scottish Environment LINK asked supporters to write personal messages to Gillian Martin, Cabinet Secretary for Net Zero and Energy, telling her why they care about Scotland’s seas, and why they want the Scottish government to protect our marine protected areas without further delay.

The messages came from across the country, from people with first-hand experience of the decline of our seas, and from people concerned about the world their children and grandchildren will inherit if we don’t act now.

Here are just some of those powerful messages…

I have lived on the shores of Loch Hourn since 1975 and for much of that time I made a living from the sea (crab and lobster fishing, mussel farming). I have watched as the marine ecology has declined to the state that now there are virtually no wild Atlantic salmon, very few mackerel in the summer and almost no cod or pollock remain.

Richard, Highland

The waters around our shores are becoming barren and wasted because of pollution and over-fishing. We must take difficult decisions to ensure that the seas around our coasts can sustain our wildlife and ourselves. This is an investment in our futures.

Pauline, Na h-Eileanan Siar

Having been a keen Scuba diver for years and seen the wonders in the seas, I have appreciated being able to see the beauty of it all. We have watched fishing boats come in and devastate the floor of the sea with their trawling in protected waters. So I strongly support the protection of marine areas.

Maggie, Clackmannanshire

Living in Macduff on the Moray Firth I am aware how critical fishing is to the local economy, but as the disappearance of the herring shoals in the last century [and] dwindling stocks of many species show, protection is essential now if the industry is to survive to benefit future generations.

Neville, Aberdeenshire

As a long-time marine biologist I am concerned at delays in implementing protections for important habitats. Out of sight should not be out of mind, as often happens with marine habitats.

Clare, Perth and Kinross

Having been brought up in the north west of Scotland I’ve seen far too much evidence of the damage caused when we don’t look after the marine environment. Our sea beds are in crisis after years and years of destruction. We must do all we can to protect what’s left.

Mairi, Stirling

It takes millions of years to create a coral reef and seconds to destroy it.

Rosemary, Edinburgh

I grew up beside the sea, the son of a fisherman who gave his life to his work and helped two of his sons to follow him. Small boats and sustainable. They gave up in mid life as they could no longer make a living. Very large fishing vessels arrived and more or less destroyed the fishing by using ten times the amount of creels my family did and that was only one boat! Please do something now or it will be too late.

Peter, East Renfrewshire

Myself and my wife go on litter picks on a regular basis to our nearest beaches. But it is the damage to the marine environment that we cannot see, cannot pick up and bin, that worries me the most.

Ian, Edinburgh

From my house I hear the sound of scallop dredgers from the Isle of Man destroying our seabed, despite the Sound of Jura being a Marine Protected Area.

Pinkie, Argyll and Bute

As a mother, I am extremely concerned about the climate crisis and its effects on Scotland and the future of my children in this country. On a recent trip to the coast I was horrified to notice the lack of wildlife, and on further investigation to learn how depleted our seas are becoming – one of our country’s most beautiful and important assets.

Aimee, Falkirk

Protecting our ocean habitats from the most destructive types of fishing is a no-brainer – healthier seas, healthier people, healthier wildlife, improved fish stocks and wildlife tourism, immense carbon capture… surely this has to be a priority for the Scottish Government.

Caroline, Highland

I have been sailing on the west coast of Scotland for 60+ years and have been very concerned about the reduction on all wildlife over that time. A very visual example of this is effect on phosphorescence which has nearly disappeared. As a boy I would see the light created by rowing and even more dramatic when diving into the water.

Mike, Edinburgh

I am a scuba diver and know only too well how amazing but fragile the sea bed and marine ecosystems are. I want my grandchildren to be able to see what I have seen.

Annette, Highland

I have had the great fortune to travel to beautiful countries that prioritise nature because they know just how vital the health of the planet’s ecosystems for the future of human health. I have seen Marine Protected Areas that are truly being protected, and I have heard the stories from local fishermen who know firsthand how effective these can be for increasing fish stocks in neighbouring waters. It truly is a win-win.

Hayley, Edinburgh

I am old enough to remember angling from the piers in Oban in the 1970s and catching Cod and Pollack that were large enough to take home to eat. When was the last time anyone went angling off these piers? I have never seen anyone do so in the last 25 years. There are simply no fish to catch there since their spawning grounds were decimated by the inshore bottom trawling that has taken place since the 1980s.

Jonathan, Argyll and Bute

We live near the coast where there was seafloor vacuuming occurring for days and nights and from which it is still, 30 years later, recovering.

Beryll, Highland

Many years ago, I was on a boat using dredges to fish for scallops. I saw the damage these did to the sea bed, so I’m well aware of how much our waters need protection.

Brian, Argyll and Bute

I was really surprised and appalled to learn that trawler fishing is still allowed in marine protected areas.

Joanna, Highland

I am a researcher working on translation and marine mammal ecology, currently on a project in the U.S. I have seen the wonders marine protection can do in North America. I wish the same for my home country, Scotland.

Sebnem, Edinburgh

I live in Orkney, so I am never far from the sea. I am increasingly concerned about the decline in animal and plant species both on land and in the sea due to habitat loss, pollution and damaging operations such as trawling. I believe we ignore these issues at our peril!

Sally, Orkney Islands

Don’t let Scotland’s marine environments become wastelands.

Julie, East Dunbartonshire

I have spent many years volunteering for Whale and Dolphin Conservation. In my time volunteering with them I have had the pleasure of seeing a multitude of marine life both above and below the water’s surface… Whales and dolphins face many threats including bycatch, entanglement and prey depletion. Implementing effective fisheries management measures throughout Scotland’s MPAs is integral to ensuring that these sensitive species thrive in our waters.

R, Na h-Eileanan Siar

All evidence suggests that when significant fishery projection measures are in place, especially those restricting bottom trawling, the wildlife, the tourism industry and ultimately the local fishermen themselves benefit from a more diverse and productive marine environment.

Paul, Aberdeenshire

I am a Scuba diver who has dived every year in Scottish waters since 1976, and have seen a decline in both species numbers and diversity in that time. I am disgusted when I see the damage done in our shallower waters by dredging activities – species and their habitats ripped up from the seabed and scattered about in ruins.

Jeff, Sheffield

I am a teacher and how can I expect the children at school to care about the environment if they see evidence that the Scottish government isn’t doing it’s very best to help.

Amanda, East Lothian

Top image: Cath Bain, Whale and Dolphin Conservation

January 16th, 2025 by morag

Here we are at the start of 2025. We’re half way through the UN Decade of Ecosystem Restoration and half way towards the Global Biodiversity Framework target to ‘take urgent action to halt and reverse biodiversity loss to put nature on a path to recovery for the benefit of people and planet’. We also have the Paris agreement target, which states that to ‘limit global warming to 1.5°C, greenhouse gas emissions must peak before 2025 at the latest and decline 43% by 2030’. So with five years left, where are we at the start of 2025, and what can we do to change things?

We know that 2024 was the first year to exceed 1.5oC above pre-industrial levels (Copernicus Global Climate Highlights 2024). The 2023 State of Nature Scotland report confirmed that 11% of species in Scotland are threatened by extinction. Key pressures on Scotland’s species are still pollution, agriculture, unsustainable sea use, climate change and invasive non-native species. Scotland’s Biodiversity Intactness Index, which measures the health of our ecosystems, is amongst the lowest in the G7 countries.

These statistics and pressures have not changed since the 2019 State of Nature Scotland report, despite another three years of policy making. How, then, can we make the kind of changes that are now even more urgently needed, within a tighter timescale and with rising evidence of irreversible change?

The changes I think we need to put in place in order to turn these statistics around include:

- Much swifter uptake of low emissions technology, particularly in transport and energy use

- Putting nature connectivity at the centre of land use decision making and planning, as an essential and non-negotiable part of our national infrastructure

- Changes in marine management to protect critical and vulnerable marine habitats

- Funding to enable investment in nature friendly farming and fishing

- Deer management to reduce deer numbers to sustainable levels

And here’s what I believe needs to happen in Scotland’s political and policy-making sphere to make these changes possible:

Building momentum

The next Scottish election is in 2026: the environment and the nature and climate emergencies in particular need to be above party politics. That means building momentum in putting in place key incentives and investment to protect against future expense and higher levels of damage.

Regulation

Actions that contribute to climate change and biodiversity loss must be regulated against, with fair protections to enable changes to be made in a timely fashion. These necessary regulations must not be derailed by party politics or electioneering.

Public goods

The public good of a healthy environment, resilient to change and able to support vital ecosystem services, must be pursued wholeheartedly by Scottish Government who cannot afford to be diverted by vested interests looking to maximise their own agendas to the detriment of the environment.

Information

Mis-information and dis-information about climate change, and the environment must be called out and neutralised.

Just transition

Scotland’s Just Transition ambitions must be delivered so that local communities can build, see and support their own sustainable future.

International leadership

Scotland’s role in international politics must be harnessed: Scotland has a reputation in global politics as a forward thinking, outlooking country with leading climate and environmental reputation. Demonstrating leadership from 2025 onwards, in our increasingly fractured world, is a key role for Scotland, helping others commit to standards to achieve a sustainable future for young people and the planet

All this must happen against the background of a new president in the United States whose anti-environment agenda runs counter to a sustainable future for the planet. With one of the world’s most powerful countries out of action on climate and biodiversity it is going to fall to other states to provide the leadership and vision the planet and our global future requires.

It’s not easy to see where this is going to come from. But it is clear that 2025 is most definitely not the time to row back or delay on action. Science and our own day to day experiences are telling us all we must act now.

Dr Deborah Long, Chief Executive at Scottish Environment LINK

Image: Calum McLennan

January 13th, 2025 by morag

Guest blog by Caitlin Paul, Marine Policy Officer at RSPB Scotland

As someone who has always had a deep love for Scottish seas and the vibrant marine life it supports, I’ve recently focused my passion on seabirds, and over the past year, I’ve become increasingly fascinated by these remarkable creatures. Every year, Scotland’s rugged coasts, islands, and towering cliffs come alive as seabirds flock to nest, breed, and raise their young. Puffins, with their striking beaks and almost clown-like appearance, perform impressive deep dives to catch fish for their chicks, known adorably as “pufflings”. Fulmars, a grey and white seabird related to the albatross, gracefully glide over the sea surface, snatching up food as they go, spitting out a surprising defence mechanism – a stomach oil they spray at predators. Meanwhile, gannets dive spectacularly into the sea, travelling as fast as 60mph into the water to catch fish.

The diversity and uniqueness of these seabirds is remarkable, yet their survival is increasingly threatened as they face a relentless wave of challenges, and it’s now widely acknowledged that urgent action is needed. Climate change and overfishing are impacting their food supplies, making it harder to feed their young. Adult seabirds die when they become caught in fishing nets as unintended bycatch, while poorly planned offshore wind farms cause death through collisions and disrupt seabird flight patterns, meaning they must fly further to feed their young. Meanwhile on land, invasive species like rats and mink wreak havoc on their breeding islands during nesting seasons when chicks and adults alike can be targeted. And on top of all of this we saw recently that avian flu can rip through colonies wiping out huge numbers in a breeding season.

These threats have had devasting impacts on seabirds. The most recent census which counts breeding seabirds across Britain and Ireland around every 20 years, Seabirds Count, published in October 2023, revealed that 70% of Scotland’s seabird species are in decline since the last census, with as many as seven seabird species experiencing declines of over 50%. On top of that, these shocking figures were taken before the recent outbreaks of Avian flu, which decimated some colonies. Results shows that the disease had a massive impact on Great Skua, with a 76% decline, and the Northern Gannet, with a 22% decline. These studies were taken into account and reflected in the recently published Birds of Conservation Concern report which reported the largest ever increase in the number of UK seabirds on the red list. Of the 23 out of 25 UK seabirds that make their home and raise their young in Scotland, 9 are now included on the red list, with 12 on the Amber list and only 2 on the green list.

It’s clear that we must act now to save our seabirds. The Scottish Government has launched its Seabird Action Plan which is now out for consultation, running until the beginning of March. This is hugely welcome and offers a critical opportunity to show public support for saving our seabirds. The plan sets out a series of actions that if delivered effectively, and with strong funding behind them, should start to reverse the fortunes of our beleaguered seabird populations.

To help seabirds recover, clear measures are needed that will:

- Protect seabird prey fish species to ensure seabirds have plentiful food

- End the ongoing bycatch of seabirds by fisheries to minimise adult seabird deaths

- Clear all Scottish seabird islands of invasive predators – and prevent them from returning – to defend seabirds and their young

- Protect the most important areas for our seabirds on land and sea to provide safe spaces for breeding, feeding, and rearing their young

- Ensure marine development delivers positive funding and outcomes for climate and nature

RSPB were part of the working group that helped develop the Scottish Seabird Action Plan and these elements are included, but the plan needs to be as robust and clear as possible and importantly lead to urgent action supported by strong funding. We are urging anyone who cares about seabirds to respond to the consultation and have suggested some additional points that we feel are needed. The link below makes it easy for you to let the Scottish Government know these measures are a priority.

In taking the time to do this you can help Scottish seabird populations build resilience, enabling them to thrive and better withstand present and future threats.

Add your voice to RSPB’s action here.

Image: Paul Turner, RSPB Scotland

When plotted over time, these data form the well-known Keeling Curve. The saw-tooth pattern of the curve (Figure 1) is particularly intriguing. It occurs because most of the Earth’s land mass is in the Northern Hemisphere and, during the northern summer, the abundant vegetation of the North absorbs a huge amount of CO2 from the atmosphere.

When plotted over time, these data form the well-known Keeling Curve. The saw-tooth pattern of the curve (Figure 1) is particularly intriguing. It occurs because most of the Earth’s land mass is in the Northern Hemisphere and, during the northern summer, the abundant vegetation of the North absorbs a huge amount of CO2 from the atmosphere. Currently, atmospheric CO2 increases by about 2.5 parts per million (ppm) each year. If the biosphere’s sequestration ability had continued growing as it did in the 1960s, the annual increase would now be smaller at +1.9 ppm per year. That’s a big difference.

Currently, atmospheric CO2 increases by about 2.5 parts per million (ppm) each year. If the biosphere’s sequestration ability had continued growing as it did in the 1960s, the annual increase would now be smaller at +1.9 ppm per year. That’s a big difference.